History

In several places around Røssvatnet, finds have been made of m.a. old stone and bone tools and traces of settlements. These are remnants of an old hunting and grazing culture without permanent settlement and which are not exactly timed but estimated to be aprox 6000 years old.

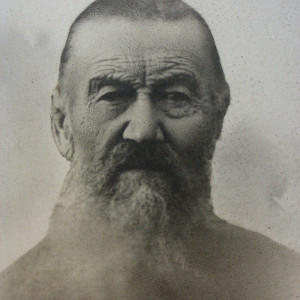

The first farms around Røssvatnet were taken up around 1750. Stekvasselv was established in 1828 by Lapp Nils Jonsen and peasant girl Bereth Olsdatter, Rana and taken over by their son Nils Nilsen, married to Karen (half Lapp).

The farm was later taken over by a new family, Kristian Nilssen from Jovatnet (Sweden), married to Kristine Lønberg. Two of their sons, Martin and Nils Kristiansen, shared the property between them. Nils married Ida From from Klippen in Sweden and had the children Helga and Harald. Harald took over the homestead and married Aasta Nerleirmo from Korgen. They had no children.

In 1985, Kari and Håkon Økland bought the farm from Aasta and Harald, who moved into a newly built housing at the farm in 1986. Kari and Håkon originally come from the Bergen area.

All the farms were basically tenant farms under Dønnesgodset where large parts were later sold to an English mining and forestry company. In 1898, after most of the forest had been taken out, the state bought back the areas on Indre Helgeland. The tenants were offered to buy the properties they had rented, and Stekvasselv was bought from the state in 1910.

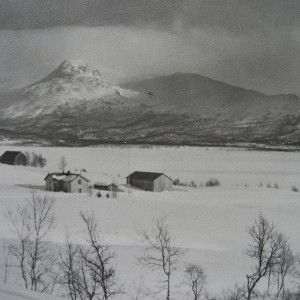

Even then, a reservation was made for damming Røssvatnet by up to 11 m, and all the builders had to waive the right to compensation in the event of a power development and regulation of the lake in order to get a deed to the properties. In connection with the regulation, which came in 1955, however, the parliament decided that a fair compensation should still be provided for loss of land and damage to buildings etc.

The story from Røsvatnet has two special features. During the time there was tenant use, the connection to the properties was weak and in many places there were regular changes of user families - they came and went their way again. The 19th century was also a hard time climatically - so years and hardships probably also helped to drive people away at times.

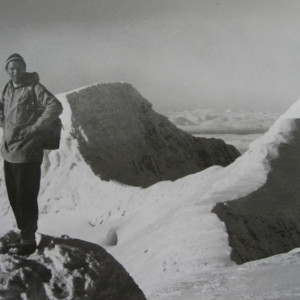

The other special feature was the contact and the migration across the national border. History shows that both for the people at Røsvatnet and on the Swedish side, the border was of little importance and the interaction was very extensive.

This was especially evident during the last war with an extensive borderless activity in the area. It was i.a. a number of Yugoslav prisoners of war who escaped from the prison camp in Korgen and crossed the border into Sweden with good help from the locals. During a raid in the summer of 1944, the Germans arrested the local men who did not escape. Some (including Harald Nilssen) were in German captivity until the end of the war.

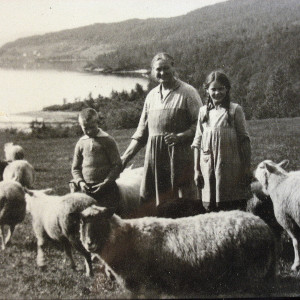

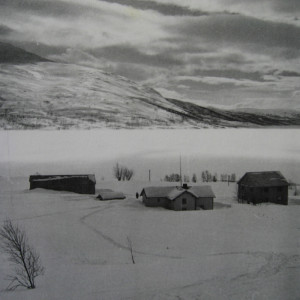

In order to survive as residents almost all the way up to the forest border on Indre Helgeland, people had to use all available resources. Agriculture provided little income, so it was necessary to provide income from additional industries. When Ida became a widow in 1933 and was left alone with two children aged 12 and 14, she started renting/ tourism. It was simple conditions, but the customers were not as well used as today. The guests came mostly from the local area on both the Norwegian and Swedish side. As few had their own cabins, and most people usually traveled little, a holiday trip to Stekvasselv was often an exclusive experience. The road connection did not come until 1968, so the journey was by steamboat or other shuttle boat on the lake in the summer or on skis or by tracked vehicle over the ice in the winter. Several other farms around Nord-Røssvatnet also received guests, but to a lesser extent than at Ida in Stekvasselv.

On all the farms around the lake, there was a production of handicraft products for sale. This was before the introduction of plastic materials, and wooden tools were consumables. Ladles and shovels from the area even found their way all the way to Husfliden in Oslo - and in considerable quantities. The Bleikvassli area is known for these rich handicraft traditions, and the local handicraft team tries to keep the tradition alive and pass on some of this knowledge to future generations.

Hunting and fishing was an important food industry with lots of birds and fish that we can only dream of today. Snare catching of grouse provided good additional income for the persistent who could withstand freezing a little on the fingers, and Røssvatnet was a very good fishing lake before the damming / regulation in 1955.